Growing together - Landschaf(f)tstadt

Prof. Dr. Silvia Malcovati and Bernd Albers in conversation with Marcus Nitschke

Prof. Dr. Silvia Malcovati and Bernd Albers in conversation with Marcus Nitschke

Marcus Nitschke

Your contribution to the 2070 competition deals with the towns of Bernau and Schwedt in Brandenburg. How did you come up with these two places?

Silvia Malcovati

We started without a precise idea. At first we started to investigate places we had already looked at under other conditions, like Potsdam or Brandenburg an der Havel. Quite quickly, however, we realized how rich and diverse Brandenburg is. We then decided to explore the radials that were of great importance for our design idea, especially the radials towards the north-east. A good hint came from the mobility experts, who pointed out to us how important the relations between Berlin-Brandenburg and Poland are for Germany at the moment. This aroused our curiosity! Afterwards we collected information and drove through Brandenburg in this direction and visited several cities.

In Schwedt we met with the director of the town museum. The museum has quite a wide-ranging documentation of the town's history and the enthusiasm of the scientists there for discovering and communicating their own town's history is great. Thus, the decision was made to consider Schwedt as an exemplary location for the competition in order to look at Berlin-Brandenburg from a more distant Brandenburg perspective. Bernau, on the other hand, is one of the towns located on the same north-east radial and can be reached in less than an hour from the centre of Berlin. At the same time, it is a town that has developed a great deal of independence, especially since reunification, and continues to develop it regardless of its proximity to Berlin.

Marcus Nitschke

An interesting thought to see this relationship also from the Brandenburg point of view!

Bernd Albers

Our chosen location at the exemplary north-east orientation also has a lot to do with Berlin and with certain historical questions that result from imperial-era planning, then later from the Weimar Republic, and finally are also connected with Nazi planning. In addition, there are the complex issues of GDR urban planning, on the one hand modern urban planning in the early phase, i.e. in the Stalinist phase of the 1950s, and on the other hand from the 1960s onwards. These are all specific realities that had a strong impact on the entire Berlin-Brandenburg region. All these backgrounds then ultimately connect the three selected areas: Berlin-Südkreuz, Bernau and Schwedt.

In Berlin-Tempelhof at Südkreuz we find housing estates on the former imperial barracks site and thus the consequences of the 1910 Gross-Berlin competition, as well as the monumental Nazi airport. In Bernau there are prefabricated buildings based on the medieval city layout, which were built from 1975 onwards after the old town was partly demolished.

Schwedt, on the other hand, is so exciting because the different models all exist synchronously there: There is a vanished residential palace, an earlier and a later GDR planning history, and a major natural phenomenon with the renaturalized forest areas and the Oderbruch National Park. The petroleum industry generated this growth in the 1950s in the first place, but has since shrunk massively. At the same time, the structures of the historic old town are only partially preserved. So in Schwedt we find the most diverse urban models in the smallest of spaces, which is why we can experiment here with alternative strategies in an exemplary way.

Silvia Malcovati

The choice of areas of specialisation also meant that all three places were a very good match. It was possible to develop a more general strategy based on these three examples, which could be very flexible for similar cases in other places. All places played a relevant role since the time of Frederick the Great and have also received a landscape infrastructure, but they have all also received their own history in the agricultural context and a more recent history with the Second World War and the reconstruction in the GDR. And for each of these layers of time, it is possible to develop different strategies to tell these stories through the projects as well.

The common thread for all proposals is rail, which is an important component for our project. We assume that traffic will largely run on rails in the future. Accordingly, the rails play a central role in the selected places. In all three places, the railway stations have contributed significantly to development and transformation over time. The places are independent, but at the same time well connected. For our overall project, these were the decisive elements.

Marcus Nitschke

While the area around the Berlin-Südkreuz and Bernau are well connected in terms of infrastructure, Schwedt is rather isolated.

Bernd Albers

The railway line currently ends in Schwedt. We want to change this and propose a connection from Schwedt along the Oder to Stettin. This would allow the important Berlin-Szczecin radial to pass through Schwedt and thus also revitalise the magnificent natural area of the Oder. In Schwedt, however, we are also debating the old town, which was largely destroyed at the end of the Second World War and not rebuilt. On the other hand, we are working on the history of the Residenz with the castle, which burnt out in 1945, was demolished in 1962 and replaced by the Kulturhaus Schwedt in 1978.

Another point is the GDR extension, according to plans by Selman Selmanagíc from 1959-60, which were then replaced by industrialised housing from the 1960s onwards. The original plan had a center, but it was not built: as the next planner, Richard Paulick realized the housing construction at the edge of the area, but the public part was never implemented. We brought this area back to life in our plans, because without a public area the radiant residential buildings make no sense. We then proposed to develop schools, research institutes or higher education facilities in this content-empty place, which could be important for the future of the whole city.

Marcus Nitschke

Was there any reaction to your competition from the cities themselves?

Bernd Albers

Yes, the people of Schwedt are obviously enthusiastic, because they obviously see a chance for the further development and better connection of their city in the context of Brandenburg-Berlin through our competition project. We meet the mayor of Schwedt Mr. Polzehl on the occasion of the exhibition in Berlin. The mayor of Bernau, André Stahl, expressed himself positively and with interest in the media the very next day, so a good response!

Silvia Malcovati

The former military sites and the station area along the Pankepark, which we looked at in Bernau, are actually currently under discussion for planning. We didn't know that for sure before, but obviously our concept is not that far-fetched and the connection to the new third ring would of course also be an enormous increase in value for Bernau.

Bernd Albers

Berlin's reactions, on the other hand, are considerably more complicated, because it is a good tradition in Berlin that district mayors do not comment on such plans, freely according to the motto: What do we have to do with it when urban planners in our district start independent considerations? However, at the opening of the exhibition in the Kronprinzenpalais, the mayor of Berlin, Michael Müller, said that he would welcome the future development of the outskirts of Tempelhofer Feld. So far, the response from Brandenburg has been much better than from Berlin. This also applies to the Minister for Infrastructure and State Planning of Brandenburg, Guido Beermann, who has expressed a willingness to talk. We will certainly meet him at the beginning of 2021, and we are already in constructive talks with the joint state planning department.

Marcus Nitschke

Can cooperation between those responsible for transport, infrastructure and urban planning set the course for the long term? Do we then have the master plan?

Bernd Albers

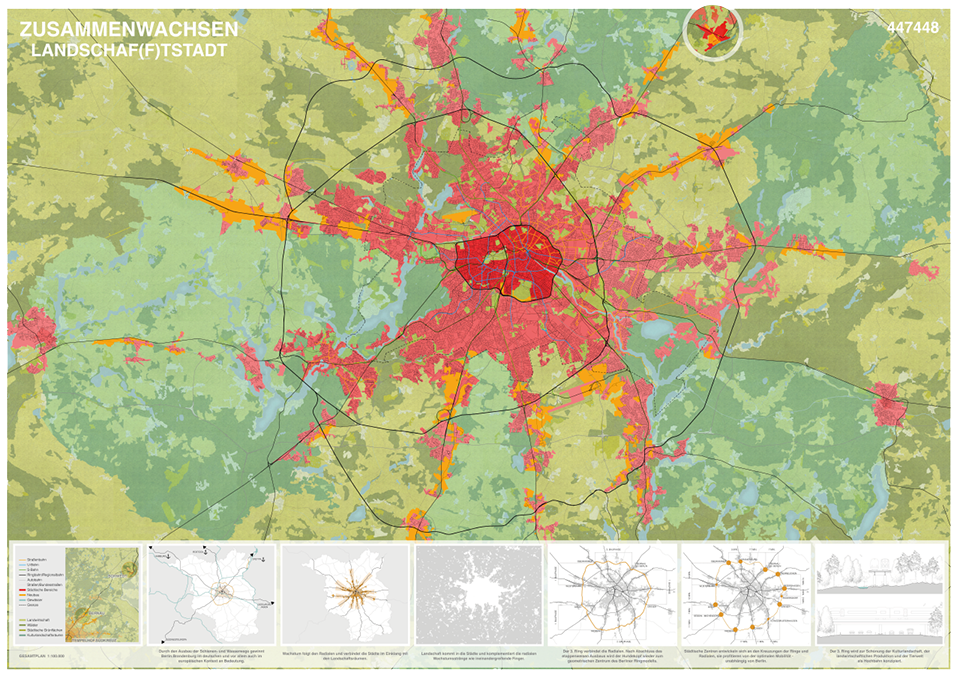

The current Berlin-Brandenburg Master Plan, i.e. the State Development Plan, did not invent itself, it is itself based on long-term phenomena and traditions of large-scale urban and transport development. We have also explicitly referred to this. We are addressing something that, firstly, already exists structurally and, secondly, is also extremely valuable. And here we come to the settlement star[1], which is the core statement for strategic planning. In the professional world it is of course well known, for laymen certainly not yet to the desired extent. We think it should be popularized as a technical term. In this context, the activities of the AIV are really worth their weight in gold, in the exhibition, in the catalogues, in the accompanying publications and also in the Metropolis Talks.

Marcus Nitschke

But it is not enough to build a railway station and a road to the town and bring some culture there. That's not a no-brainer yet.

Silvia Malcovati

We have developed the idea that the settlement star can be significantly improved and strengthened by a 3rd rail ring. The individual nodes can thus be connected better and faster, much more independently of Berlin than today. Today, if you want to travel from Bernau to Oranienburg by public transport, you have to go via Berlin. This third ring already exists in part, but the aim is to create a ring closure in the medium term. Such a ring closure can certainly be done in phases, even partial sections already bring considerable relief. Since the connections in the west are already much more advanced, we have not designed a completely new 3rd ring in our draft, but have connected it in the west with the existing 2nd ring.

Marcus Nitschke

After all, the concept of cultural landscapes does come up....

Bernd Albers

The issue of landscape must be further differentiated in the future, between landscape protection issues, agriculture in various forms and the recreational landscape. These things also play a role. We have used the term "cultural landscape" to describe them, knowing full well that Lenné also used the term, but meant it differently, perhaps on a different scale. If you look more closely, you will notice that the green wedges pass over places that are not at all green today. We wanted to show a perspective in which some places are developed, but some are not. Only then will the idea of the settlement star prevail in the long term. Here we consistently orientate ourselves on the railway radials, the motorway ring is still there, but in perspective it no longer plays a major role and should not be further developed.

Silvia Malcovati

We selected as development sites only those areas that are not nature reserves or forests along the railway radii, i.e. areas that can actually be realistically built on. At the end, we looked up: how many square metres that is. We came up with an area for about one million additional inhabitants, just in the area of the settlement star.

Marcus Nitschke

The city limits that existed within the current Berlin 100 years ago have since been dissolved by the creation of Greater Berlin. Is that also your plan for the cities around Berlin?

Silvia Malcovati

The idea is that not only Berlin but also the medium-sized towns in Brandenburg grow. It is not about urban sprawl, which is why we have given the project the title "Growing Together". Brandenburg an der Havel, for example, has enormous potential for residential and also industrial sites in the centre of the city, which are available and also in the interest of the city, but still the city is not growing. Optimizing the railway connections would certainly accelerate this process.

Marcus Nitschke

Back in the early 1990s, people in Berlin thought: Now the great growth begins, but it never came. And now, 30 years later, it is again retarding, not least due to the Corona pandemic.

Bernd Albers

That already went down at the beginning of this year. Of course, this also has a bit to do with the fact that an atmosphere was created that said: Actually, the city is full and everyone who comes in here is a nuisance. This is a strange position that has little to do with an enlightened urban way of thinking. Of course, this has atmospheric effects on future developers. If a municipality hardly wants to develop an idea and only hints at fragmentary themes with pressure from outside, but does not develop an overall plan from this, this is also disastrous for public participation. The urban context can then not be seen by the public! That is why we developed the exhibition Berlin 2050 - Concrete Density from the university context together with our colleagues Barbara Hoidn, Wilfried Wang and Jan Kleihues back in 2017 and showed the exhibition Berlin 2050 - Space and Value in 2018.

In the second exhibition, we mainly tried to develop a strategic position in order to show exemplary scenarios at different locations in Berlin with the student works, but at the same time to locate them in a grand plan.

Marcus Nitschke

Do you think that the polycentric structure of Berlin and the theme of Greater Berlin still make it difficult to hold the idea of the city of Berlin together in one's mind? Unlike Vienna or Paris, there is no general idea set in stone in which the inner city is clearly defined and everything around it has grown on.

Bernd Albers

I think the much-invoked polycentrism is also partly a myth of Berlin's history, which was essentially promoted by the experience of division before 1990. From the 20th century onwards, i.e. from the time when the city became Gross-Berlin, one can certainly speak of a polycentric city, but the singular historical core remains undisputed. You only have to look at the map, there it is clearly recognizable.

Silvia Malcovati

In the discussions about the competition results and the exhibition in the Kronprinzenpalais, I heard that participation processes and participatory processes should be brought to a higher level through the overall show. Currently, one understands participation within one's own neighborhood, but such a discussion within a district can also be dangerous, because a minority there feels affected by decisions that come from above. Instead, this participation should be brought to the level of Greater Berlin or even Berlin-Brandenburg, so that the concrete measures that can take place in individual places are not understood as extraneous operations, but as part of the overall plan. So we should try to create a common enthusiasm for a more general strategy. Because this cannot be taken for granted, I was all the more pleased that both the discussions on the competition results and on individual places will now follow this overarching strategy.

Marcus Nitschke

One more question about the development of ideas for your project. Who was involved in your project, or how interdisciplinary were they - and did that work?

Silvia Malcovati

Yes, that worked very well. The 1:100,000 scale is a scale that hardly any of us normally work at. That in itself is a challenge, which made collaborative work necessary. We worked with workshops, especially in the first phase that worked very well, where we sat around a table and everyone could work together. But also afterwards when we couldn't meet on site because of Corona. I think everyone involved had the opportunity to contribute their competences equally and these are also well visible in the contributions. We as architects and urban planners, the landscape architects around Günther Vogt and the mobility experts from ARUP contributed in equal parts to the development of the common idea.

Bernd Albers

This is not the first time we have been on the road in this constellation as a competition team. We have made experiences together in modified constellation. The team spirit and coordination have worked very well. With Günther Vogt and Arup, I won the Antwerp-Linkeoever ideas competition in 2017, and in 2019 I won the competition for the Königsufer in Dresden together with Günther Vogt.

Marcus Nitschke

I have looked at the three designs and would like to discuss with you in more detail what role the apartment blocks play.

Especially for Tempelhof, the question arises: Was there a conscious decision for the size and proportioning of the blocks? And what is the inner life of these blocks?

Silvia Malcovati

Our models were the competition results from 1910, where not only the urban space is depicted, but also the architecture. We realized pretty early on that this level of figurativeness and concreteness of the architecture was no longer necessary for us. We definitely didn't want to specify what architectural form the city should have. At the same time, our team agreed that the goal should be spatial, that is, three-dimensional representations.

We did not want to stick to the representation of diagrams, numbers or abstract schemes, but to form urban spaces that, without getting lost in architectural detail, define as accurate a city silhouette as possible. That's why we decided to use the technique of a collage of aerial photographs.

This was by no means a foregone conclusion. Beforehand, we experimented with different forms. The decision was made, on the one hand, to create a certain uniformity between the three areas and, on the other hand, to create this effect of the images.

The projects are relatively different: In Berlin at Südkreuz, we intentionally depicted the apartment blocks as extruded construction fields. We didn't want to show classic Berlin apartment buildings with courtyards and peripheral buildings, but simply potential building fields. The residential buildings are located along the S-Bahn, which we have moved to the north. This creates an island between the S-Bahn and the autobahn. In our plans, the S-Bahn runs parallel to the autobahn, so that a connection with Tempelhof is created and a completion of this urban fabric is made possible by the interrupted infrastructure.

Mixed building forms with offices and workshops can be envisaged here. The aim was to create a kind of overarching structure that has significance not only for Berlin, but also for Brandenburg. The Tempelhofer Feld already plays a major role. Of course there is a perception here from the point of view of the neighbourhood, but people from all over Berlin and Brandenburg spend their free time there on weekends. We have tried to reinforce this role by adding a large public building on the edge of the field. The arch of the airport connects to the north, the three towers to the south form a city gate at the intersection of Tempelhofer Damm and the crossing railway tracks.

The projects in Bernau and Schwedt, on the other hand, are presented in a more realistic and concrete way. The reason for this is the significantly smaller scale and the strategy of urban repair. This gives the proposed interventions scales in which the projects could be refined one step further typologically.

Marcus Nitschke

Thank you very much for the interview.

1] The planning basis for the development of Berlin's surrounding areas is referred to as the Berlin Settlement Star. The name Siedlungsstern alludes to the radial or star-shaped spread of settlements from Berlin in the Brandenburg hinterland.